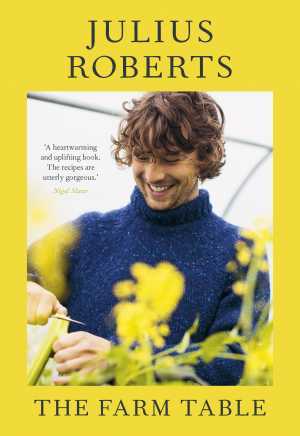

To go against the grain in your twenties is scary. I’m not talking about drinking ale when your friends drink lager or living south of the river when your pals live north. I’m talking about upping sticks and leaving the city, buying three pigs on the agricultural equivalent of eBay, and starting a farm with zero experience. Tempted?

Julius Roberts was. A stint as a chef at London’s Noble Rot, with punishing hours, stressful shifts and a notable lack of sunlight took its toll, and the lure of a self-sufficient life in the Suffolk countryside beckoned.

Fast forward eight years, and he now runs a small farm on the Dorset coast that's bountiful with chickens, sheep and goats. He’s accumulated a devoted Instagram following, starred in his own Channel 5 TV show, written a cookbook named The Farm Table and already has another book deal in the pipeline. It’s not been without its steep learning curves, though – farming is life and death, and as a first-generation farmer armed with just Google and YouTube, learning on the job and making mistakes is par for the course.

We caught up with him to talk leaving London, the highs and lows of rural life, his new book and, er, how to trim a goat’s toenails.

The farmhouse in Dorset where Roberts lives with his family

Elena Heatherwick

What made you leave London?

I loved living in London. I grew up there, had loads of friends there, and loved the food scene and the socialising that comes with it. I left not because I disliked London but because I didn't love working as a chef. You love it, and you loathe it. It's one of those things that's very exciting – the adrenaline is something else, and the camaraderie is super fun. The speed you have to learn in the restaurant world is epic and relentless, and the job takes a huge toll with the long hours and the heat of the kitchen.

I worked at Noble Rot, and because you were arriving and leaving when it was dark, it would be an 18-hour shift without seeing the sun. It was a punishing job but kind of awesome. I have so much admiration for chefs, and I long for that time as well. I didn't leave it sorely but knew I couldn't do this forever.

We used to go and have our cigarette breaks towards the end of the shift. You'd be halfway through tidying up, most orders are through, and I'd be sitting outside with my head chef. It took me a month to sum up the courage to say I was leaving because they were like my brothers – you spend so much time together and go through hell. It is like being in the army or something. So I left with a very heavy heart and have regretted it, slash I love what I’m doing now. But I left Noble Rot to do this, so it was more of a leap of faith to a different style of life than because I hated what I was doing.

Do you ever miss London?

Yes and no. I desperately miss my friends; that's been a huge sacrifice. That's where I grew up and where all my friends ended up after we all went to university. I left at that very formative time, 23 years old, when everyone started living together. You're getting your first jobs, relationships, breakups, and first houses together – it’s such a special time. And that was so hard to watch from afar.

I'm quite a good solitary person, and I'm strong about my journey, but that is a tough thing to leave behind, and your best mates become best mates with each other, and you're like, oh. It’s a big deal leaving that solid. I miss the restaurants, the galleries, the culture, the beautiful view out my window, but there's not much else. Luckily, I absolutely love where I am now, so I'm very happy here, and I've got such a big sense of purpose, which can pull you through anything.

How did you go about setting up the farm?

I quit my job in the restaurant, kind of fumbled around in London for a while, trying to work out what on earth I was going to do and then decided to buy some pigs and move to the country. It was a completely off-the-cuff, mad decision. The whole story has been a journey of learning.

Roberts and his goats

Elena Heatherwick

… where does one buy a pig?

Essentially, there's an eBay, like a Gumtree, for animals. I just jumped on Pre-loved, typed in Mangalitza pigs, found some woman in Essex who was rearing them, and went and bought them. She turned up a month later, at which time I'd been learning to build fences and made sure they had water. They walked in, and that was it – you just had to learn.

Why did you start out with pigs?

I left my job in July, had a nice summer with friends, and then it was winter by the time I moved. It was a crap time to grow anything. I couldn’t even put my spade in the ground because it was too hard. I felt like everyone had chickens, and it’s not exactly like farming; it’s not a big step. Whereas pigs were a big deal. You have to keep them for quite a long time. They're big animals but are also famously easy to look after and clever. So pigs give you a lot; there's a lot of opportunity for relationships there, and that was very formative.

It was eye-opening that these animals looked me right in the eye and were very individual and full of character. It became a really important part of what I was trying to do in sharing the fact these animals are really alive, and that’s something we forget. They’re individuals like us.

What was the scariest part of setting up the farm?

The stuff that gets scary is life and death – I mean, farming is life and death. Last year, I had this disease on my farm called orf, which is this nasty kind of herpes-esque illness that can go through sheep and goats and their whole face just gets covered in these awful scabs that you can also catch yourself because it’s a zoonotic disease that can pass from species to species. So, if you have any little cut on your hands, it can get in through that. When you’ve got 50 of your sheep and lambs coping with this thing, you can catch it, and you've never dealt with it before; it’s a pain. What can happen is if the lambs get it on their lips, they then give it to the mother's nipples, and they can't drink because the mum will just kick them off because it hurts. So it's not life-threatening itself, but the symptoms can cause awful things. And as someone who's never dealt with that before, you are just like, what on earth do I do here?

I think things you’ve never dealt with before are the scariest. You've got this life-threatening thing, suddenly moving like wildfire through your flock, and you realise how on the edge you are. My ignorance is the best bit about my journey. I've just been learning for the last eight years, which is such a good feeling. But then, when you are on the edge, it’s not quite so fun; it's more like holy shit. Plus, there's a lot of people watching online at the same time.

A field on Roberts' Dorset farm

Elena Heatherwick

Farming is a real generational thing. So most farmers learn from their dad and have just grown into it, and they've seen it all before. My favourite thing about what I do is that I don’t know what I'm doing. It can be scary at times. I've made a lot of mistakes, and some of those have resulted in animals dying, which is a pretty big deal. But what a way to learn when it really matters.

How do you deal with these first-time problems?

Honestly, Google and YouTube – you’ve just got to figure it out. For the orf outbreak, it was gloves on and full waterproof jackets, and my brother and I sprayed each other down. At the end of every day, you've got to be careful. You open a gate with it on it, and then if you’ve got a little itch on your hand and scratch it, you’ve got the disease. When you can’t itch your nose it’s amazing how itchy it gets.

What’s your favourite part about the farm?

Nature is just so epic, inspiring, and beautiful, and I love being part of it. For so many people, it doesn’t affect their day-to-day lives unless Mother Nature dictates whether you wear a jacket or take an umbrella with you. For me, nature affects what I eat, when I get up, and what my jobs are – it's ever-present. And I think that's very special. I love that.

I really enjoy a sunny day because it completely changes how my day is. We've had these incredible storms, and I was going out onto the hill and just sitting there in the wind, just going whoah – that kind of stuff is very special.

I also love the connection with animals; they are amazing things. From my chickens to my sheep to my goats, they are all so funny and characterful. There are so many individuals out there, which is really fun. It is busy, and you are kind of fulfilled, but it's also quite peaceful.

Gardening in the greenhouse

Elena Heatherwick

Leeks in a wheelbarrow

Elena Heatherwick

What's the funniest thing that’s happened on the farm?

Every spring, all animals give birth. You are dealing with 30 sheep that will give birth in a couple of months and maybe ten goats this year. And sometimes things go wrong. A mother might not have enough milk, or she might die and leave her lamb with no one there to look after it – then it falls on you. So we've had goats and sheep living in the kitchen by the aga.

Normally, these animals are in a flock living together, which is a massive part of who they are, so when you’ve got a single animal, it’s desperate, and you can’t have them on their own – so you have to be their parent. One of the funniest things was this little goat called Nettle, who slept in the bedroom in a little basket by the bed. One time, I came into my room and pulled up my duvet, and she was just there, completely passed out underneath, hidden. Just doing that deep, slow baby breathing – that kind of thing just makes me laugh so much.

Also, the goats have peeled the wallpaper off my entire kitchen. There's obviously something in the old limestone wallpaper, which has a mineral that they love. They’re only this tall off the ground, but they’ve worked their way around the whole room.

Do you think you’ll ever let the farm go?

It might grow and shrink and change in stature, but I’m totally committed to this life. At the moment, I've got quite a lot of animals, and it's quite a lot of work. Maybe a part of me is trying to prove myself as a farmer, not just a smallholder. But there are times when you're like, Jesus, I can't go away because I'm stuck. My brother helps me on the farm, so he's there to pitch in. But he works three days a week here and then is in London for the rest. You can feel a bit penned in, and that affects the way you farm.

Take cows – I’ve always wanted to have a milking cow to go out in the morning and get my own milk each day and make butter and cheese, but then you are stuck having to milk a cow every single day. You can't take a day off making that milk whether you're there or not. And if you don’t milk the cow, it’s just going to sit there and mess with her udders. So, in terms of the future, I think there's room for it to grow, and maybe I will get a milking cow one day, but after a few years, I'll be like God, I'm not doing that again.

A greenhouse on the farm in Dorset

Elena Heatherwick

What’s the worst job on the farm?

Trimming toenails. See, sheep and goats have toenails on their hooves. If they lived wild, they’d be going miles every day, climbing over mountains and rocks, so they’d wear them down a lot. Whereas, in a smaller field on grass, they don't wear down enough, so you have to trim them. When it’s cold and wet, and they have mud and shit stuck in their nails, they can get diseases and all sorts.

So, you’ve got to trim them. You have to turn them upside down, and no animal likes being upside down. You've got to flip each one from all four hooves while they're fighting you, and you are bent completely upside down. If we've got 50 or 70 sheep, that'll take us four hours between two people. Kicking up at you and scratching your face. You're spraying them with this special spray to kill the bacteria, and then they hit you, and it covers you. It’s the worst.

That's one of the things no one told me about when I started. I remember calling the guy I got the goats from and asking why they were limping, and he asked me if I’d cut their nails. And I thought, what does he mean mean? I had no idea goats had toenails.

Roberts and one of his goats

Elena Heatherwick

How do you trim toenails?

A special, big toenail clipper.

How is it being a part of the UK food system?

It's hard to make any money. I mean, there are times when you are struggling to break even. I think farmers get pinched by the supermarkets and how cheap food is. Now prices are going up, and I think we’re all feeling it – it's really expensive for food writers or chefs to test recipes. Plus, it’s not really the farmers who are getting that, and that's a big issue. The food system is not in a good way at all and luckily, I'm kind of shielded from that because we're just a small farm, and I sell my meat to individuals. Farming has one of the highest suicide rates there is in the UK. It’s a tough profession where your profit margin is right on the line 24/7, you have to work your arse off every day, and there’s little support.

Farmers need us to care where our food comes from and make the right choices. When you're shopping, it's important to look for food that has actually come from England. It's a scary time because the government has done a lot of undercutting in the trade deals after Brexit. Because we farm to high standards in the UK, we’re now importing meat farmed to a much lesser standard because it’s cheaper. There’s a lot to talk about on that front.

The big message of my cookbook is about seasonality and looking for quality produce and local food, so that's kind of my way of talking about this stuff. But yeah, farms are struggling and need our support in any way possible. A great way of doing that is by looking for local, great seasonal produce and caring about what you eat.

What’s your favourite recipe from your cookbook?

There’s a pork belly recipe with prunes and onions that’s really slowly cooked, which I’m proud of. I’m also not a pastry person or a pudding chef, so doing the pudding part of my book was really hard, and I put a lot of work into it. I think that they are some of the best recipes in the book. There’s an apricot sponge, like an upside-down little cake, where you steam it in the oven. When you rip off the sponge top, the apricot juice spills out the sponge. It's just so juicy and awesome.

Pork belly with prunes from The Farm Table

Elena Heatherwick

One ingredient you can’t live without?

Olive oil. I'm never without olive oil, and when we don't have olive oil, we're really like, shit, what are we going to do. Lemons would be the other. I use a lot of lemons. I love acidity – everyone knows about salt for seasoning, but acidity is another really important part. The difference between purple sprouting broccoli with salt and purple sprouting broccoli with lemon and salt is vast. You will always find onions, olive oil, lemons and butter in my kitchen.

If you could only have one meal for the rest of your life, what would it be?

I mean, there's nothing worse than asking a cook what their favourite thing is because we make a job of loving it all. I ate a dish for the first time the other day called Hainanese chicken rice. It’s so good for this time of the year. You fry skin-on chicken thighs to get a lovely crispy skin with shallots, garlic, and ginger. Then, you put in rice and broth and gently poach the meat. It makes this fatty, brothy, chickeny rice dish that’s really clean with a tonne of aromatic flavour. It’s just like a warm hug.

Chicken and ricotta meatballs from The Farm Table

Elena Heatherwick

Roberts on the farm in Dorset

Elena Heatherwick

What’s in store for you this year?

I’ve started another book, which is quite exciting. It's a bit more written and will focus on the day-to-day farm life – like a diary with the food woven through. So I'm just writing a diary every day about general farm life – about the storm that came, the sheep that escaped or the goat that trashed my car. The stories in the book then directly influence what I'm cooking in the kitchen. So when it’s cold and grey, it takes you towards a lovely nourishing soup, and you give the food a real story and purpose, which is quite fun.

I’m also desperate to get some pigs this year, and we’re doing some really cool stuff with nature on the farm, working with The Dorset Wildlife Trust. As a farmer, I believe you have to be a guardian of the countryside and the land you have. It's not just about supporting humans; it's about supporting all sorts of nature and humans together. So here we're trying to have the right amount of animals that don't take everything from the land, and you're leaving a lot of the bugs, birds, voles, foxes and stuff. We're doing quite a lot of what's called meadow restoration and woodland management, where you are just trying to increase the biodiversity of the habitats to support all sorts of other animals because nature is struggling at the moment in the UK.